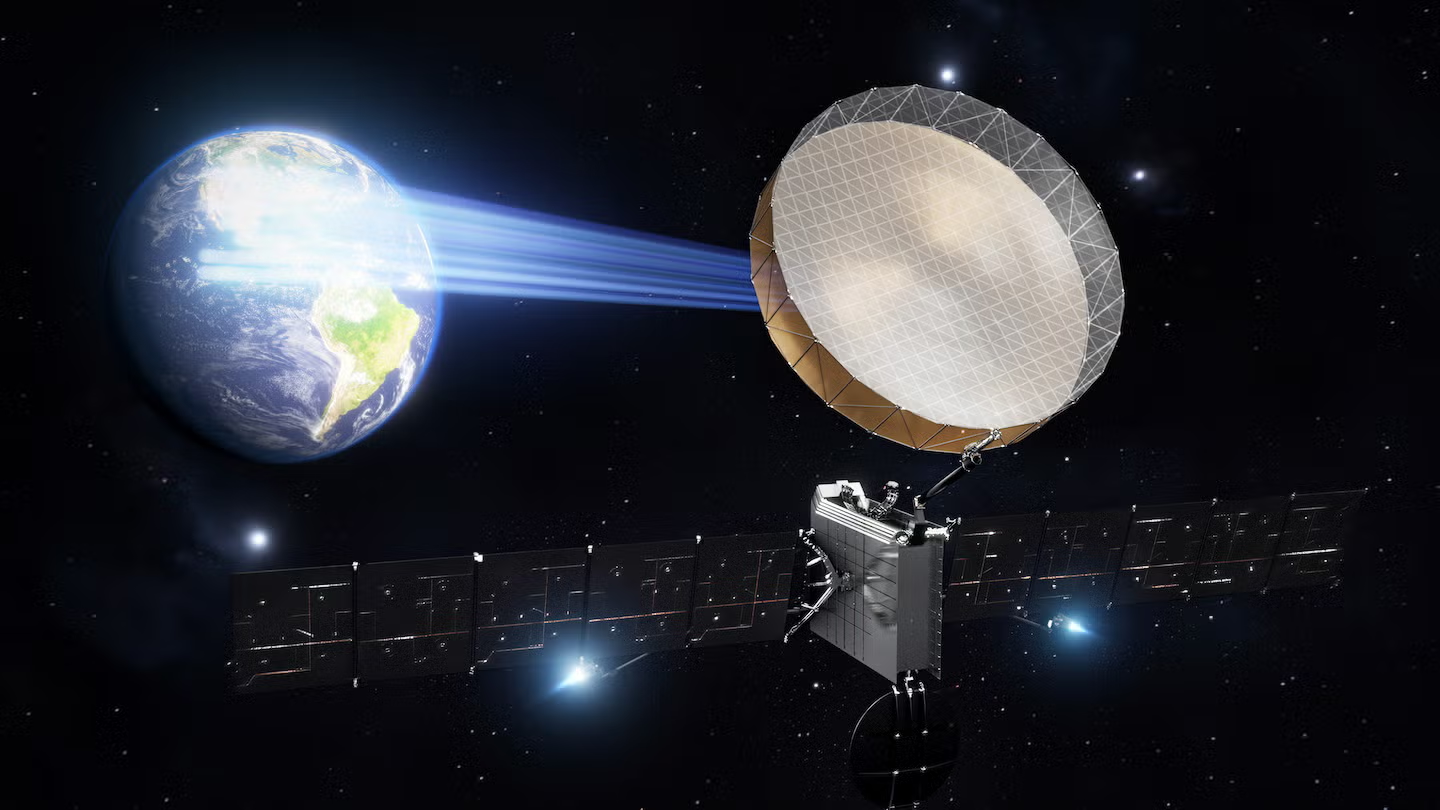

Astranis is developing a geostationary commercial satellite called Omega that is being pitched to the U.S. military for broadband communications. Credit: Astranis

By Sandra Erwin,

Published by Space News, 4 September 2025

For decades, the military has relied on large, multi-ton satellites for global communications from geostationary orbit (GEO), a prime location 35,000 kilometers above Earth that provides unique advantages for connectivity and security.

Big satellites still remain indispensable, but the U.S. Space Force is now turning to smaller GEO platforms to broaden its options.

The Protected Tactical Satcom-Global (PTS-G) program, officially launched this summer, marks the military’s first significant attempt to deploy constellations of small satellites in the geostationary belt.

This shift comes as electronic warfare capabilities advance globally, forcing military planners to rethink how they protect critical communications links. The Pentagon worries that dependence on a handful of large, expensive satellites present attractive targets for adversaries. By contrast, the “swarm” approach being pioneered through PTS-G distributes risk across multiple smaller platforms, making it more difficult for opponents to neutralize communications capabilities.

Alongside the resilience that comes with greater numbers, PTS-G is also aimed at lowering costs and changing the economics of military satcom.

Cheaper access to orbit and a more dynamic commercial sector are reshaping how the Space Force weighs its options. In years past, the economics of launching to GEO encouraged building a few large, highly capable satellites rather than many small ones.

By maximizing every launch — putting as much capability on each satellite as possible — government and industry operators could make the most of limited launch opportunities and ensure the high reliability from platforms that are costly to replace or service.

Lower cost small satellites, up until now, have mostly been built for low Earth orbit (LEO) and have fueled a boom in LEO communications. These satellites orbit much closer to Earth, and the coverage area of each is small, so many satellites are needed to provide continuous global service.

For all the appeal of LEO, geostationary satellites are still attractive as they offer continuous coverage over large areas with fewer platforms. And the economics are also quickly changing as the industry is now producing smaller and more affordable satellites designed for GEO that can be produced and launched faster.

A new procurement playbook

The convergence of smallsat advances and military needs for resilience set the stage for PTS-G as a bet on small satellites for secure military communications.

Beyond the technology, PTS-G is also about rewriting the procurement playbook.

Rather than locking in a single contractor for the life of the program, the Space Systems Command has set up a 15-year indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contract worth up to $4 billion. A pool of five suppliers has been selected to compete for follow-on production awards, with the first batch, dubbed “Swarm 1,” expected to set the tone for the rest of the program.

“Our PTS-G contract transforms how SSC acquires satcom capability for the warfighter,” said Cordell DeLaPena, program executive officer for SSC Military Communications and Positioning, Navigation and Timing.

The program embraces the use of “commercial baseline designs” to meet military needs, he said in a statement. PTS-G aims to deliver secure broadband using a proliferated architecture — multiple small satellites working together — to provide resilience against electronic warfare and physical threats. Small GEO satellites — typically 300 to 1,000 kilograms — also promise faster deployment and more flexibility.

The Defense Department awarded an initial task order collectively worth $37.5 million in July to five companies — Astranis, Boeing, Intelsat, Northrop Grumman and Viasat — for designs and demonstrations to be completed by early 2026.

The approach represents a break from the way the Pentagon has traditionally procured communications satellites. Historically, military GEO satcom programs have involved a single manufacturer building a handful of large, highly customized spacecraft, each designed to operate for decades. That model has tended to favor incumbents with decades of performance history and the ability to navigate complex government requirements.

The Wideband Global Satcom (WGS) and the Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) are prime examples of the traditional, bespoke approach to military satellite communications. Both programs are highly customized, multi-ton GEO satellites focused on delivering capacity and coverage for the U.S. military and its allies. The rigorous specifications, unique hardware and government-driven engineering effort reflected a philosophy in which satellites were meticulously tailored to meet precise operational requirements even if it meant long timelines and higher cost.

PTS-G marks a deliberate shift from that model.

“It’s encouraging that you have the department wanting to use commercial services to a greater extent than it has in the past,” said Sam Wilson, director for strategy and national security for the Center for Space Policy and Strategy at the Aerospace Corporation.

Increased use of commercial space capabilities, he said, “could serve as a forerunner for defense acquisition reforms and greater use of nontraditional defense providers.” Wilson noted that the Defense Department continues to evaluate different business models as it seeks to balance commercial space innovation with government needs for operational control of assets such as satellite constellations.

The PTS-G approach would be a hybrid model — government-owned satellites built using commercially-derived technologies and manufacturing processes. This differs from a purely commercial service model, in which the military leases capacity from privately-owned constellations.

A competitive field

Erin Carper, senior materiel leader for tactical satellite communications at Space Systems Command’s Military Communications and Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Program Executive Office, emphasized the program’s focus on commercial space tech.

“PTS-G’s goal is to maximize cost efficiencies by leveraging commercial bus designs to the fullest extent possible,” she said. At the same time, the Space Force wants to ensure “backward compatibility with current user terminals.”

In practice, this means no vendor has a guaranteed pipeline. It can also mean performance in the early phases could determine who stays in the competition.

The service’s use of the word “swarm” is noteworthy as well. That term is familiar in LEO constellations, where dozens or hundreds of satellites share coverage, whereas GEO satellites tend to operate independently.

A GEO swarm implies multiple coordinated satellites in similar orbital slots, sharing the workload and providing redundancy, so losing one spacecraft doesn’t mean losing an entire region’s coverage.

The military’s embrace of small GEO satellites follows a trend in the commercial sector.

Boeing, one of the companies selected for the first phase of PTS-G, in 2019 started offering smaller satellites for geostationary orbit as a solution for operators reluctant to invest in multi-ton spacecraft amid changing market conditions and the competitive pressures of LEO megaconstellations. Terran Orbital, a satellite manufacturer owned by Lockheed Martin, last year announced plans to produce a new line of buses aimed at the small GEO market.

Another competitor in the PTS-G vendor pool, Astranis, is a San Francisco-based startup that has carved out a niche in the commercial small GEO market, building 400-kilogram satellites for targeted regional coverage. The company has already launched five small GEO satellites for commercial satcom operators. Other companies such as Swissto12 and Saturn Satellite Networks are preparing to launch GEO smallsats over the next two years.

While these small GEOs aren’t designed to replace the massive, high-throughput satellites still anchoring many networks, they promise lower costs and rapid deployment. Smaller buses can be launched in batches in a single rocket, reducing per-unit deployment costs.

PTS-G satellites must operate across both X-band and military Ka-band frequencies, each serving distinct operational requirements. X-band communications are important for their reliability in adverse weather conditions, making them useful for operations in maritime environments, for example. Military Ka-band supports high-capacity communications and provides access to spectrum specifically reserved for government use, reducing the risk of interference from commercial users.

In addition, Space Force leaders want the program to support both users on satellite networks that run the Protected Tactical Waveform (PTW) ground-system software and those that do not. PTW is an anti-jam communications protocol developed by the Space Force to keep data flowing under hostile interference. While some satcom ground systems in military networks use PTW, not all have.

The initial PTS-G design and demonstration phase will be followed by production contracts to be awarded to at least two firms in 2026 for Swarm 1, with a projected launch in 2028. A third competition and award for a second batch of PTS-G satellite capability is planned for 2028 with a launch planned for 2031.

The Space Systems Command has not disclosed how many satellites will be in Swarm-1 or in subsequent orders.

Opportunities for commercial space

Although Astranis is new to the military market, through Small Business Innovation Research contracts, the company has been working with the Space Force to explore integrating the PTW software and military Ka-band capabilities into its design.

“We’ll be proposing a government-owned, commercially operated model,” said John Gedmark, CEO and co-founder of Astranis. “This allows the government to take advantage of the infrastructure we already have.”

Gedmark said he’s hearing from military customers that despite wider use of commercial satcom services across DoD, there is still unmet demand for broadband communications. “When we look at the needs of the warfighter and the various service branches, including the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, we see the demand for dozens of these satellites. Everyone needs more broadband capacity and they need it now.”

At the end of the current phase of the PTS-G program, he said, Astranis plans to deliver a proposed design and “details on our production capabilities.”

Boeing, meanwhile, is highlighting its experience building commercial and military satellites, including the WGS constellation the company has produced for over two decades. There are 10 WGS in orbit, and two more are in production. Boeing also makes communications satellites for commercial satcom operators such as SES.

“We are building on a technically mature product line to deliver a solution that meets the capability and schedule requirements of the Space Force,” said Michelle Parker, vice president of Space Mission Systems Business at Boeing Defense, Space & Security. “PTS-G complements our existing programs. It builds on our heritage of delivering resilient, anti-jam satellite solutions for military applications.”

Northrop Grumman said its PTS-G design will leverage its commercially available GEOStar-3 satellites for secure X-band and military Ka-band communications. “Northrop Grumman’s PTS-G solution will provide a lower-cost, rapid and commercially acquired solution,” the company said in a statement.

SES’ acquisition of Intelsat has created another competitor in SES Space and Defense, now led by David Broadbent, who was previously president of government solutions at Intelsat. Broadbent characterized the PTS-G selection as “a significant milestone for the company as we step into the role as a prime integrator,” though the company declined to comment about its specific approach.

SES, a major GEO satellite communications provider, has been transitioning toward smaller satellite architectures in medium Earth orbit.

The fifth PTS-G competitor, Viasat, did not respond to requests for comment before publication.

Budget and timeline pressures

The schedule for the PTS-G program is aggressive.

The Space Force’s fiscal year 2026 budget request includes approximately $239 million for PTS-G, funding design, demonstration, engineering, manufacturing and testing of Ka-band and X-band prototypes.

Whoever is selected in 2026 to produce the first swarm is expected to be ready to launch in 2028. Compared to traditional defense procurement cycles that can span decades, PTS-G is attempting to compress development and deployment into a few years.

The broader implications of PTS-G extend beyond military communications. If the program demonstrates that small GEO satellites can effectively deliver the resilience and cost advantages promised, it could trigger a broader transformation across other satellite programs.

In a report on Space Force budget trends published in early August, Wilson noted that a “growing emphasis on commercial space capabilities aligns with broader acquisition reforms the administration has been pursuing to favor nontraditional defense firms,” as directed in an executive order issued in April.

Further, recent legislative proposals from both the House and Senate Armed Services Committees mandate that the Pentagon comply with congressional requirements to “prefer commercial goods and services in federal procurement.”

PTS-G may end up being an example the Space Force can point to.

See: Original Article